Growth of a Rivertown

Steamboat Era - Immigration - Slavery - Agriculture

Early Weston wharf — drawing by Dr. R.J. Felling

Steamboat Era

The earliest steamboats passed by the bend in the river that was to become Weston, MO (in 1837) on their way north to multiple posts of the American Fur Trading Company. Those first boats took supplies north and returned to St. Louis with furs.

By 1840 steamboats regularly stopped in Weston. At its busiest, Weston’s port saw over 250 steamboats a year during navigable months to drop off supplies for Weston and Ft. Leavenworth and to take the hemp and tobacco from Weston’s agricultural economy on their return south.

photo of Riverboat in Montana that stopped at the Port of Weston

Early settlers

Immigration

From chapter III- Weston Queen of the Platte Purchase by Mrs. B.I Bless, Jr.

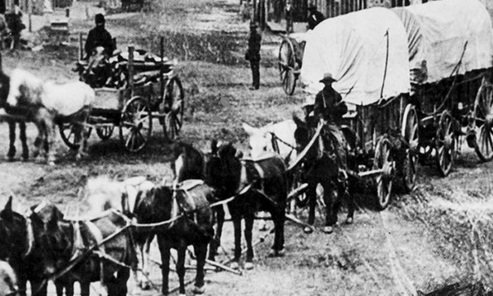

“Weston’s first settlers came by covered wagon; later a three month steamboat trip brought them. Some admitted that the most fearsome part of the journey was the "livery” from the landing at the Weston wharf to their future home behind oxen teams. Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia furnished the first immigrants.”

Weston’s first settlers were of western European descent. Early history and family stories chronicle Germans, Austrians, Irish, Scots, Swedes, French and more— They packed up their possessions and left all they knew, hoping for a better life. Some of the settlers from Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia brought enslaved Africans.

Photo from “Weston- Queen of the Platte Purchase” 1968 by Mrs. B.I. Bless, Jr. (Bertha Bless)

The accompanying text for the photo above from circa 1960- “This deteriorating three-story Inn and Tavern stood on Platte City Turnpike about halfway between Weston and Platte City. When the anti-slavery forces became troublesome, slaves were unloaded at Rialto, from steamboats, and placed in farm wagon beds. They were covered with hay or straw or sometimes light merchandise and brought to this Inn. While their masters regaled themselves at the gaming tables and bar upstairs, the slaves were chained to rings in the stone walls of the cave, the bare outline of which is seen at the extreme lower left. Next day the slaves were auctioned off at the big front door. Only a small portion of the cave remains standing. All the rest has disappeared.”

Corner of Main and Thomas Street

Slavery

Enslaved Africans were brought to early Weston by their ‘owners’ who depended on the slaves to help them work the labor-intensive hemp and tobacco crops and to establish claims to land. Most settlers and able-bodied slaves spent back-breaking and long days cutting trees, burning and removing stumps, clearing an endless supply of rocks from fields and then cultivating the land to stake claims that only the white settlers could procure.

Most of the tens of thousands of bricks that can be seen today on homes and buildings in and around Weston were made by slaves. Some of the handmade bricks are now being repurposed as part of a courtyard next to the city park— to memorialize the many enslaved souls who, without their toil, Weston would not have prospered as it did.

You can participate in the Buy-a-Brick campaign to support that worthy cause.

Enslaved people were buried in a segregated section of the City Cemetery, now Laurel Hill Cemetery, to the left and down the steep hillside inside the entrance. Slave and free black grave markers were lost or destroyed through the years. In 2021, a Methodist Minister’s wife and Weston citizen, led a campaign to place a large stone with the names of most but sadly not all the African Americans- slave and free- who are buried there. The marker can be seen today a short distance into the entrance of Laurel Hill Cemetery on Welt Street.

Tobacco is harvested by hand. Stop by the museum to see a large model of a tobacco barn and a full explanation- with photos- of how tobacco was grown and harvested.

The Fair and Equitable Tobacco Reform Act of 2004 (P.L. 108-357), signed by President Bush on Oct. 22, 2004, ended the Depression-era tobacco quota program and established the TTPP. The program provided annual transitional payments for 10 years to eligible tobacco quota holders and producers. Thus- Weston relinquished its place as a major tobacco producer and as a site for tobacco auctions.

Agriculture

The backbreaking work of clearing land of thick forests and rocks; the farmer’s friend or foe- weather; the steamboat transportation that was often unreliable with boiler explosions, fires, snags and sand bars; the politics of exploiting enslaved people; all that and more— farmers managed through the years.

Hemp was the major crop from 1840 through the end of the Civil War. Because of the intensive labor involved, hemp was no longer as profitable when enslaved people were freed. The final hemp crops were shipped from Weston in 1885.

Tobacco crops on a large scale began in 1894 and was produced in Weston under a federal government quota system and profitable into the 20th century. It can’t be overstated how important tobacco was to the economy of Weston for over 100 years. Weston was home to the only tobacco auction west of the Mississippi River until the last auction in 2004.

Weston area farmers today produce thriving fields of corn, soybeans, wheat, and truck farm vegetables. A local popular Christmas Tree farm, orchards, several you-pick fruit and vegetable farms with strawberries, apples, pumpkins, plus farm animals for children to pet— all bring multitudes of families to Weston throughout the year.

The museum has files, photos, and displays with fascinating stories and information. Plan a visit! There is no admission cost so stop in to browse, and then return soon.

A fading symbol of Weston, MO agriculture is the tall, weathered, frame tobacco barn. Farmers built the barns to house tobacco after it was harvested late summer. The tobacco stalks with leaves would be speared on tobacco sticks and the sticks would be hung on multiple tiers in the barns. The tobacco would dry in the fall and winter months until the leaves were at the best humidity to strip from the stalks and take to market. Weston, MO had the only tobacco auction west of the Mississippi River until the last one in 2004.

The barns were built with large doors on either end of the rectangular building. Long narrow hinged doors for vents covered multiple openings on both long sides that could be opened or closed depending on weather. When the doors were all open, the distinctive brown tint of tobacco leaves could be seen hanging from the multiple tier rails and the pungent smell of tobacco broadcast the season and the crop.

Most of the Weston, MO barns dated from the twentieth century, a time when the USDA was promoting a standardized barn design to aid the tobacco curing process. Even with the recommended specifications, farmers often built the barns to suit their needs with appendages for storage, stripping sheds where the tobacco was stripped and prepared for market, equipment, and occasionally animals.

The photos are of a tobacco barn in the Weston Bend State Park that is adjacent to Weston, MO. The barn was built in 1931 and has an interesting display about the crop that brought financial wealth to the community but is no longer locally significant.

You can see a large scale model of a tobacco barn in the lower level of the Weston Historical Museum- Main Street, Weston, MO.